Last month in Venezuela’s capital city of Caracas, a cup of coffee would have set you back 2 million bolivars. That’s up from only 2,300 bolivars 12 months ago, meaning the price of a cup of joe has jumped nearly 87,000 percent, according to Bloomberg’s Café Con Leche Index. And you thought Starbucks was expensive.

But that was July. Prices in Venezuela are doubling roughly every 18 days. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) now projects inflation to hit an astronomical 1 million percent by the end of this year. This puts the beleaguered Latin American country on the same slippery path as Zimbabwe a decade ago and Germany in the 1920s, when a wheelbarrow full of marks was barely enough to get you a loaf of bread.

Venezuela’s socialist president Nicolas Maduro—who recently survived an assassination attempt involving several explosive-laden drones—announced recently that the country plans to rein in hyperinflation by lopping off five zeroes from its currency. If you recall, Zimbabwe similarly tried to combat soaring prices of its own by issuing a cartoonish $100 trillion banknote—which in 2009 was still not enough to buy a bus ticket in the capital of Harare.

Without structural governmental reforms, a new bolivar is just as unlikely to steady Venezuela’s skyrocketing inflation or remedy its crumbling economy.

Gold Could Save Your Life

So where does this put gold? At some point, hyperinflation gets so ludicrously out of control that discussing exchange rates becomes pointless. But as of July 30, an ounce of the yellow metal would have gone for 211 million bolivars—an increase of more than 3.1 million percent from just the beginning of the year.

My point in bringing this up is to reinforce the importance of gold’s Fear Trade, which says that demand for the yellow metal rises when inflation threatens to destroy a nation’s currency—as it’s doing right now in Venezuela. A Venezuelan family that had the prudence to store some of its wealth in gold would be in a much better position today to survive or escape President Maduro’s corrupt, far-left regime.

In extreme cases like this, gold could literally help save lives.

Such was the case following the fall of Saigon in 1975. If not for gold, many South Vietnamese families might not have managed to escape the country. A seat on one of the thousands of fleeing boats reportedly went for eight or 10 taels of gold per adult, four or five taels per child. (A tael is slightly more than an ounce.) Gold was their passport. Thanks to the precious metal, tens of thousands of Vietnamese “boat people,” as they’re now known, were able to start new lives in the U.S., Canada, Australia and other developed countries.

Venezuela’s Once Prosperous Economy Destroyed by Corruption and Mismanagement

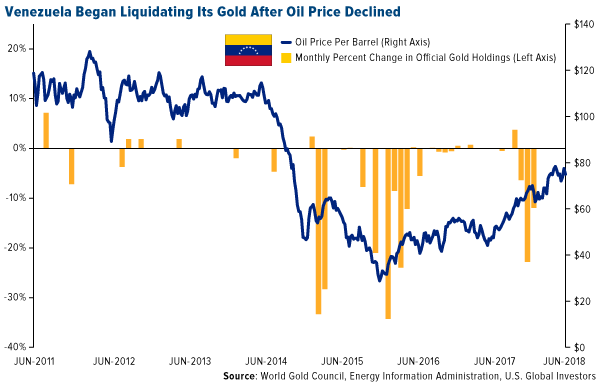

But back to Venezuela. Amid the corruption and mismanagement, the only thing helping the country pay its bills right now is gold. Two years ago, it had the world’s 16th largest gold reserves. Today it stands at number 26 as it’s sold off more than half its holdings since 2010. While countries such as China and Russia continue to add to their holdings, Venezuela has been the world’s largest seller of gold for the past two years.

It’s hard to remember now, but as recently as 2001, Venezuela was the most prosperous country in all of South America. Like Zimbabwe, the OPEC nation is rich in natural resources, home to the world’s largest oil reserves and what’s believed to be the fourth largest gold mine. Oil exports account for virtually all of its export revenue.

In 2016, Venezuela was the third largest exporter of crude to the U.S. following Canada and Saudi Arabia, but with output in freefall, this is changing rapidly. For the first time ever in February, Colombia sold more crude oil to the U.S. than its eastern neighbor did. And in June, Venezuela’s state-owned oil and gas company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), informed at least eight foreign clients that it would be unable to meet supply commitments. According to GlobalData, production is on track to fall to only 1 million barrels per day by 2019, down from 3 million a day in 2011, meaning the petrostate might soon have nothing left to deliver.

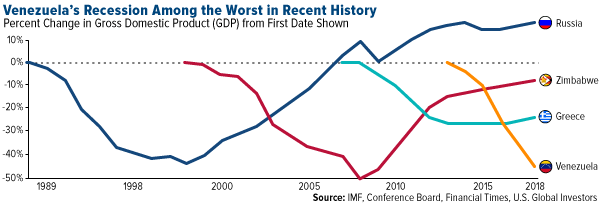

President Maduro now has the ignoble distinction of reigning over an economic recession that rivals the very worst in modern history. Last month, the IMF forecast that the country’s real gross domestic product (GDP) would fall 18 percent this year—the third straight year of double-digit declines.

A mass exodus of young, working-age Venezuelans, many of them college-educated, is unlikely to help. Estimates of the number of people who have fled the country in the past two years alone range from 1.7 million to as high as 4 million.

Their escape is no easy task, as numerous international airlines, citing rampant crime and a lack of electricity, have canceled all flights in and out of Caracas. The only U.S. carrier still operating in the country is American Airlines, which offers a single daily flight from the nation’s capital to Miami. Just two years ago, there were as many as 40 nonstop American flights, not to mention those of rival carriers, between the two cities—a sign of just how dramatic and swift Maduro’s mismanagement has been in crippling Venezuela’s once-robust economy.